Investor News

Australia leads metallurgical coal exports

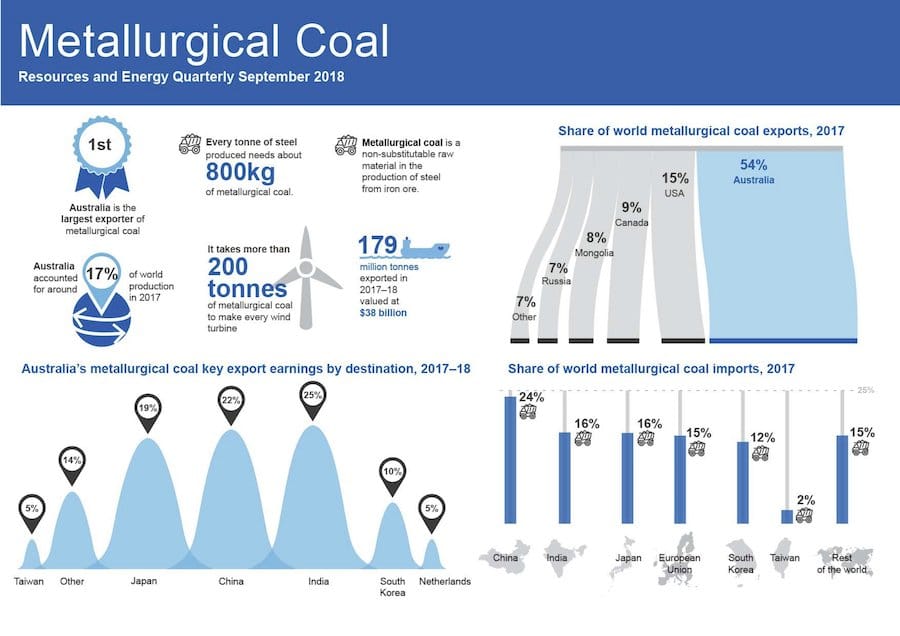

The latest 'Resources and Energy Quarterly' published by Australia's Chief Economist highlights Australia's role as the worlds leading exporter of metallurgical coal.

The report also projects India will surpass China as the largest importer of metallurgical coal from Australia by 2020.

Neither point is surprising.

What is interesting is this line from the below infographic:

Metallurgical coal is a non-substitutable material in the production of steel from iron ore.

The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science is correct; there's no substitute for metallurgical coal in blast furnace steel making.

The blast furnace route is the dominant primary steel making route globally. It requires high-grade lump iron ore and metallurgical coal. There's no way around it when it comes to blast furnace chemistry and physics. The blast furnace route is a 'brute-force' carbon-based iron oxide reduction process that operates between 1300°C-1500°C.

This is where HydroMOR comes in.

HydroMOR utilises a different chemical pathway; hydrogen.

The result is a lower temperature process that decouples iron making from metallurgical coal.

This has raised the question; is our HydroMOR process a threat to Australian metallurgical coal exports?

Realistically, while we believe there is a significant opportunity for HydroMOR following successful R&D outcomes in India, we do not see HydroMOR as a material threat to Australia's absolute growth in met coal exports to India.

The main reason is scale.

India is aiming to increase crude steel making capacity by 165MTPA, from 135MTPA to 300MTPA by 2030.

To become a threat to Australia's existing met coal exports, we would need to deploy more than 13 million tonnes of HydroMOR capacity per year between now and 2030.

Given we're entering the R&D phase shortly, and the commercial phase is yet to follow, this level of rollout is impossible in the given timeframe.

How much HydroMOR capacity could we ultimately deploy in India?

Obviously, a lot of work needs to occur before we can really answer that question, but the answer lies in India's iron ore problem.

India has abundant iron ore reserves. The problem? Its ore is softer compared to the hard, high-grade lump ore Australia is known for. This creates a significant amount of fines.

The traditional iron-making method, the blast furnace, needs hard lumps of iron ore, high Fe concentration (>62%), and high-quality metallurgical grade coal.

And while iron ore fines can be processed into pellets or briquettes, the cost of doing so is often a negative-sum game depending on the prevailing price and availability of high-quality lump ore. Right now, there are no buyers. India’s iron ore fines are stranded.

As it stands, there are an estimated 150 million tonnes of low-grade fines stockpiled around India. Translated, that’s ~90 million tonnes of iron, more than 15 years of Australia's current steel industry output.

Further estimates indicate that 30% of iron ore mined is too fine for blast furnace use.

HydroMOR is the ideal solution for dealing with this 'waste' stream.

Read more...

Resources and Energy Quarterly

The Resources and Energy Quarterly contains the Office of the Chief Economist’s forecasts for the value, volume and price of Australia’s major resources and energy commodity exports. A ‘medium term’ (five year) outlook for Australia’s major resource and energy commodity exports is published in the March quarter edition of the Resources and Energy Quarterly. The June, September and December editions contain a ‘short term’ (two year) outlook.